How and why was FRACTAL different from the many projects that aim to produce climate information for decision-making? We asked Chris Jack, from the Climate System Analysis Group, what set FRACTAL apart.

Climate science has greatly evolved in the past 20 years. After an early focus on producing numbers, data, and running models, there was a growing realization that data alone wasn’t necessarily improving decision-making because of the difficulty in translating and understanding it in decision contexts. Thus, in the last decade, there has been a strong shift towards making data, primary information and science outputs more relevant and more applicable to decision-making.

FRACTAL provided crucial insights in understanding why, even when relevant information is available, good decisions are sometimes still not happening.

For a long time climate scientists have had quite a naive view of how decisions are actually made – we kind of imagined that the information we provided landed on a table somewhere, with all the right people around it, engaged in a rational and well structured process that resulted in a decision.

In practice, decision making on climate information is more complex. Thus with FRACTAL we took a deep dive into understanding decision-making, exploring formal and informal governance, working with people who are making decisions in southern African cities, and looking at how information flows through a network of people when decisions are made.

The other area we dived deeply into with FRACTAL was the problem space. We identified what we called the “burning issues” for each city, and we tried to go much deeper than simply finding the relevant climate variables or statistics. For example, for an issue such as flooding in peri-urban areas, we tried to understand the problem, what decisions would need to be made, what possibilities were on the table, and only then we did begin to identify what science would be relevant and how we could turn the science into information so that people could engage with it.

It was a much deeper unpacking of the context than I’ve ever seen in a climate science project.

Instead of spending a lot of time on complex climate science analyses, we explored how existing science efforts are useful, looking at issues such as understandability. Sometimes simpler science may result in better decisions than very complex science, because it’s understandable and people can engage with it.

Other key factors are transparency and trust, and we worked quite a bit around building trust between scientists and decision-makers, creating sort of networks in which people trust each other and by extension the information that is being shared through these networks.

In summary, rather than just focusing on more science, we looked at existing information and tried to find value in it. Rather than just exploring information needs, we also looked at connecting people, knowledge and perspectives. Rather than just building capacity, we built relationships and trust. This new way of framing how we do climate science is what sets FRACTAL apart.

First published on ProSus Magazine, November 2019

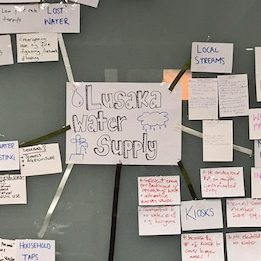

Photo: Unpacking Lusaka’s water supply during a learning lab