GLOCULL: Globally and LOCally-sustainable food-water-energy innovation in Urban Living Labs. GLOCULL is a Belmont Forum funded international team of researchers and stakeholders aiming to develop an Urban Living Lab approach for innovations in the FWE nexus that are locally and globally sustainable. START is supporting Stellenbosch University, Centre for Complex Systems in Transition involvement in the Belmont Collaborative Research Action.

Food and nutrition insecurity are some of the key pressing challenges in Cape Town with a food system largely characterised as unsustainable. In 2017 Statistics South Africa reported that 24% of the population in the Western Cape Province experience severely inadequate access to food. Cape Town, one of the eight South African metropolitan cities, is located in the Western Cape Province and is home to 57% of the province’s population. South Africa reported in 2017 that 32% of the Cape Town population are at risk of food hunger. This is a pre-COVID scenario that has been negatively impacted by lockdown and the curtailment of economic activities dating back to the 27th of March 2020.

The concentration of power by a small group of private actors has, to a large degree, resulted in food and nutrition insecurity experienced by the most vulnerable sections of the population in Cape Town who cannot afford food. These private actors, mainly large-scale formal producers, agri-processors, and formal retail enjoy concentration of power and control the food system. While the government plays a central role in driving policy development and implementation, the status quo has been configured in such a way that limits fundamental shifts in the food system.

Food insecurity and massive disparities in food access and consumption continue to be challenges in Cape Town. In general, the food system does not equally service Capetonians and the broader citizens of the Western Cape Province. Poorer households in particular continue to experience food insecurity.

Government top-down and silo approaches to addressing food systems challenges remains in evidence across the food system with very changes taking place. The gloomy status of food security in Cape Town has encouraged small pockets of innovation by social actors and NGOs. Urban food gardens in low-resourced communities have, over recent years, emerged as one innovative local solution to address inequalities in food. The food growers behind these gardens often sell produce to local residents through the informal food sector. There are a number of growers that sell produce to the formal food sector, but this is challenging for a number of reasons. Firstly, the access to the market is highly controlled by the five big retailers in South Africa who source their produce from a small number of large-scale producers. Secondly, urban growers face opposing city regulations have limited mandates to influence the food system. Agriculture policies accommodate to a greater extent established large scale produces located in rural regions of the country. Strong food system mandates at the provincial and national levels tends to support large-scale food production and agri-processing which tends to be located outside city boundaries. As a result, access to key resources such as land and water remain a challenge for urban growers.

As such, sustainability of urban gardens in Cape Town remains a challenge.

While food gardens in Cape Town will not solve systematic challenges in the food sector, they do have potential to address aspects of the food system challenges given that 60-70% of Capetonians get food through the informal sector. While this is a significant role played by the informal sector, very little has changed to enable ease of doing business. Researchers and urban growers have over the past years experimented with innovative ways to bring change towards sustainable food systems through localised production.

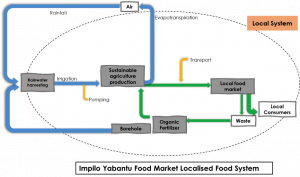

The Ikhaya Food Garden non-profit organisation is one of the bottom-up food systems innovations experimenting with growing organic vegetables in garden located in one of Cape Town’s low-resourced communities, Khayelitsha, with a recorded figure of 89% of households either moderately or severely food insecure. The garden aims to supply organic produce to local residents through hosting locally Impilo Yabantu Market. Impilo Yabantu means “people’s health” in one of the local South African languages, Xhosa. Ikhaya Food Garden also sells produce directly to customers at the garden.

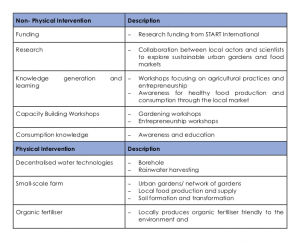

In partnership with Stellenbosch University, Centre for Complex Systems in Transition, Ikhaya Food Garden co-designed the market model as well as documented what is working and what requires change – the desired state being a thriving sustainable model for hosting frequent food markets for the local community. Physical and non-physical interventions are described in the table below.

While food insecurity is challenge in Khayelitsha, the project is interested in producing food in a way that is sustainable with a localised approach that does not waste water and energy resources.

The co-design and co-implementation process of the project between academics and food producers requires a partnership between the two constructed through transdisciplinary mechanisms to generate knowledge about sustainable practice. This mainly involves building capacity attributes for academics and food growers to act sustainably in their everyday decision-making and practices through education, practical and interpersonal competencies, and activating new behavior-patterns. Capacity attributes for sustainable urban food production built in the project include:

- incorporating sustainability thinking in every-day practices,

- connecting to network that aims to act sustainable,

- ability to market sustainable food produce to local community,

- practical skills for developing partnerships,

- ability to develop long-term sustainability plan for a food market and a food garden, and

- ability to communicate sustainable solutions to government officials and other key food actors.

These sets of capacity attributes distilled in this project will provide insight as to efforts required to build sustainable urban food gardens as well as sustainable transdisciplinary approaches.